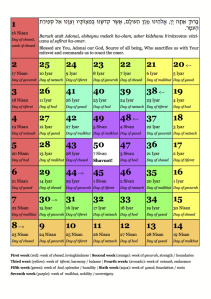

Reflections and Lessons from the Havdalah Circle of Boyle Heights

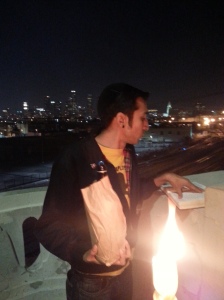

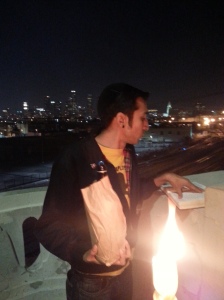

Havdalah at the 6th Street Bridge, overlooking the city. Dare to make anyplace a sacred space! Punk rock Havdalah with Shmueli Gonzales and Jesse Elliott. Los Angeles.

As Shabbat comes to an end, I always make my way back towards the town and people I love. Towards the arches which over the years have become know as my station and post. And leaning against the metal arches of the bridge, high upon the Los Angeles Sixth Street Viaduct, I bask in the final and lingering rays of the Sabbath’s sun. And then I wait. Wait for the sun to set. I wait, for my buddies to count the stars and declare that it’s time. “One… two… three stars… it’s time!”

And then out from my ubiquitous bag I take these items. A Hebrew prayerbook, a dried etrog and clove bundle as a D.I.Y. “spice-box,” a kiddush cup and a multi-braided havdalah candle.

Havdalah – the ritual for closing the Jewish sabbath – has always been one of my favorite Jewish traditions. And over the years I have always tried to make pause to observe it with the people I care for the most. There is something very warm and loving about the ritual. Something which has always captivated me, and has interestingly drawn my friends in along the way.

Indeed most of my local friends are not Jewish, and consider themselves firm atheists. I am one of the less than a half-dozen Jews who are currently connected to Boyle Heights. And among them few Jews, I’m pretty sure I’m the only one who is strongly religiously observant. Nonetheless my friends – Mexican-American, Anglo, African-American, Asian, and especially my older Jewish friends of mine who were born in classic Boyle Heights – they all encourage me to do Havdalah. And they also love to include themselves in this ritual, which is so part of my life. Even the occasional homeless Jewish person.

In a very fundamental way, over the past few years my adventitious return of Jewish rituals such as this back to this historical multi-ethnic neighborhood – one which itself has such a deep and rich Jewish history – has really touched people. These are symbols that the light of Jewish life and expression has not been fully extinguished here. It reminds the community that we haven’t forgotten those who went before us here, who also embraced these enrapturing acts.

“Hinei el yeshuati eftach v’lo efchad! – Behold G-d is my salvation, I will trust and not fear! – for G-d is my might and my praise – Hashem – and He was a salvation for me.”

A revelation of how much a part of my routine and how meaningful it has become to others came when I ran out of supplies recently, and my punk rocker friends went scavenger hunting to find me items to make havdalah with on the spot. Knowing that my joy would not be complete without this moment, they just had to find a way to improvise! A very sweet and revealing moment for me.

To say the least, I learned after that to never be caught without supplies again. This week we will use a new candle. A long bees-wax candle with nine wicks all braided together.

Standing at the observation point overlooking the skyline of Los Angeles. Lingering at what could well be considered the gates of the city, we make our stand. My prayerbook placed upon a decorative niche of the bridge as a shtender. As I stand there above the train tracks and the water of the river, suspended between heaven and earth. There I light the wicks. I wait for the flames to take hold, until it comes to a roaring flame like a torch. Before I hand it over to one of the guys, who are ready to take it in hand and hold it high.

Overlooking the city I can’t help but be reminded of the Talmud section from which we get this most ancient custom of using candles as a torch. In Pesachim 8a this conversation takes off with the sages calling attention to why we use bright lamps and lights, namely to search. Our sages draw from the prophets, on how G-d will search the city of Jerusalem with lamps, in order to punish the complacent; those who are indifferent to realities of good and evil. (Zepheniah. 1:12) With a light that is meant to search out for justice.

And furthermore the Talmud suggests to us that this light represents our need to extend a light to search out for other precious souls, drawing from the scriptures:

|

“The human spirit is the lamp of Hashem

searching all the most deepest parts of ones being.”

|

נֵר יְיָ, נִשְׁמַת אָדָם; |

חֹפֵשׂ, כָּל–חַדְרֵי–בָטֶן. |

|

|

Proverbs 20:27

|

So among this most motley crew of eastsiders, among the most unlikely of circles I make my stand, and I bless from this place. From this cultural corner of Los Angeles my heart calls home, I stand with other diamonds in the rough. Among other unique souls worth searching for. This tradition challenges me to search people out as with a penetrating light, looking deep into their souls to find their worth.

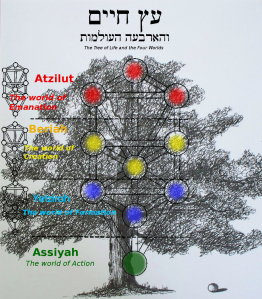

I love the symbolism of this candle. Braided it represents the separations between the spiritual and physical wolds, and mystically symbolizes how they come together; to be intertwined. It represents the separations between the sacred and the secular, and also how they come together. That they are both needed in our lives. A symbolism which is poignant as we step out of the sacred joy of Shabbat, and into the secular workweek which we have before us. As we stand at the cosmological gates between the sacred and the secular.

I love the symbolism of this candle. Braided it represents the separations between the spiritual and physical wolds, and mystically symbolizes how they come together; to be intertwined. It represents the separations between the sacred and the secular, and also how they come together. That they are both needed in our lives. A symbolism which is poignant as we step out of the sacred joy of Shabbat, and into the secular workweek which we have before us. As we stand at the cosmological gates between the sacred and the secular.

And it also represents the souls of people, who are distinct; we are each our own flame, but in unity we must intertwine ourselves for the purpose of a mitzvah. Together our small and single flame becomes a roaring torch; for we are much better together and united.

As we stand I see the flames of the candle reflected in the awe of the guys faces and in the twinkle of their eyes. As Jesse exclaims, “Look how brightly you can see it, even from far away! It really is like a torch!”

As he says these words I keep in mind what the Talmud further relates to us as to why this is the best way to make havdalah, with the use of a torch:

|

“Surely Raba said: ‘What is the meaning of the verse: “And his brightness was as the light; he had rays coming forth from his hand: and there was hiding of his power.” (Habbakuk 3:4) To what are the righteous comparable in the presence of the Shechinah? To a lamp in the presence of a torch.’ And Raba also said: ‘[To use] a torch for havdalah is the most preferable [way of performing this] duty.’”

|

והאמר רבא מאי דכתיב (חבקוק ג) ונוגה כאור תהיה קרנים מידו לו ושם חביון עוזו למה צדיקים דומין בפני שכינה כנר בפני האבוקה ואמר רבא אבוקה להבדלה מצוה מן המובחר:

|

|

Talmud Bavli, Pesachim 8a

|

The sages then call attention to our own souls, in the light of this mitzvah. It says to consider ourselves as though we are search lamps. But as for this torch, to consider it as comparable to the presence of G-d. That our souls are as bright as lamps, standing next the presence of G-d – in the most radiant light of the Holy One, blessed be He. As the true torch, the most beaming of lights, the Shechinah – it is as thought the surrounding presence of G-d is made manifest among us as we stand with this light.

When I extend the lights of this multi-wicked candle I am welcoming the presence of the Shechinah – the presence of G-d to this place. Welcoming the all-encompassing spirit and the life of all the worlds to this place. For a moment spirituality becomes an almost tangible atmosphere.

“Shalom and Son’s,” a kosher food and wine distribution business still operating in the Boyle Heights Flats.

The Talmud further instructs us upon this subject of havdalah. That we need to include at least three distinct blessings, but adding no more than seven; not more than the days of the week, whose cycle we are renewing with this act.

I take my drink in hand as the ceremony begins. Today we are without wine or kosher grape juice, which is a shocking thing. Considering that underneath us, and just a few hundred feet to the east of us, right in the Flats of Boyle Heights, on Anderson sits a kosher food and wine distribution plant with their Kedem trucks parked in their gates. One of the few present-day Jewish businesses of Boyle Heights is “Shalom and Son’s,” which by way of this neighborhood supplies so many Jewish tables in Los Angeles with this staple of wine as a liquid symbol of joy. Yet we are all out after days of celebrating, and they are closed for shabbos. So the wine-cup goes away and a beer is placed squarely in the palm of my hand.

And then I begin to rhythmically chant the words of the prophets and psalms which begin the ritual of havdalah (in the western Jewish tradition):

|

“Behold G-d is my salvation, I will trust and not fear – for G-d is my might and my praise – Hashem – and He was a salvation for me. You can draw water with joy from the springs of salvation. (Isaiah 12:2-3) Salvation is Hashem’s, upon your people is your blessing, Selah. (Psalm 3:9) Hashem, Master of legions, is with us, a stronghold for us is the G-d of Jacob, Selah. (Psalm 46:12) Hashem, Master of legions, praised is the man who trusts in you. (Psalm 84:13) Hashem save! May the King answer us on the day we call. (Psalm 20:10)”

|

הִנֵּה, אֵל יְשׁוּעָתִי אֶבְטַח, וְלֹא אֶפְחָד, כִּי עָזִּי וְזִמְרָת יָהּ יְיָ, וַיְהִי לִי לִישׁוּעָה. וּשְׁאַבְתֶּם מַיִם בְּשָׂשׂוֹן, מִמַּעַיְנֵי הַיְשׁוּעָה. לַײָ הַיְשׁוּעָה, עַל עַמְּךָ בִרְכָתֶךָ סֶּלָה. יְיָ צְבָאוֹת עִמָּנוּ מִשְׂגָּב לָנוּ אֱלֹהֵי יַעֲקֹב סֶלָה. יְיָ צְבָאוֹת אַשְׁרֵי אָדָם בֹּטֵחַ בָּךְ: יְיָ הוֹשִׁיעָה, הַמֶּלֶךְ יַעֲנֵנוּ בְיוֹם קָרְאֵנוּ:

|

As we stand upon this massive chunk of concrete and metal, I chant the words in Hebrew. For me, the words become more alive here, at this spot and among these friends of mine. This is our “mishgav lanu” – this is our stronghold, our fortress, our hideout. It is only right that I come here to make such a mitzvah. The rain has just passed, so the river is filled with water. You can hear the faint rushing below, as my soul draws water with joy from the springs of salvation. The sights and sounds are all so vivid.

Aside from the sound of an occasional train below and the rush of a bus at our side, the only other sounds are from the cars passing over the bridge to and from downtown. And the faint and distant rumbling of the freeways which are integral to this viaduct. Though this is the choice spot to observe this city from the eastside, we are among the few people who come here, as mostly its just locals and homeless people. More often these days the occasional hipster does come out of the arts district, but sadly they usually take one look at us edgy punkers standing upon the bridge and nervously turn around instead.

Aside from the sound of an occasional train below and the rush of a bus at our side, the only other sounds are from the cars passing over the bridge to and from downtown. And the faint and distant rumbling of the freeways which are integral to this viaduct. Though this is the choice spot to observe this city from the eastside, we are among the few people who come here, as mostly its just locals and homeless people. More often these days the occasional hipster does come out of the arts district, but sadly they usually take one look at us edgy punkers standing upon the bridge and nervously turn around instead.

Indeed, this viaduct it is the most picturesque location in the city. But for those people who are more of a boutique style of urbane, this is not a regular destination. It’s a wild adventure, because its lodged right in between the infamous Skid Row and the much ignored ethnic community of Boyle Heights. We are standing on the main artery through the “rough neighborhoods.”

But still we hold the torch high, and with full conviction in my voice I declare in the holy tongue: “Hinei el yeshuati eftach v’lo efchad / Behold G-d is my salvation, I will trust and not fear!”

And for a moment, walkers take pause as they pass. And the drivers who are weary, my friends say they can catch a glimpse of the awe on their faces as well as they pass. No fear nor even dreary eyes for just a moment. Just awe and wonder as people witness this amazing sight. As we perform the ceremony cars honk at us as they go, joining in like urban “amen”s.

I can hear Zero-Renton say, “Look, those westsiders standing at Mateo are pointing towards the torch! They see it all the way over there!”

And then we continue with the next words, which I say in Hebrew and English. These words which are meant to be repeated by the participating crowd. An all-inclusive and universal phrase which extends the light and joy of Judaism to all who dare to embrace and befriend it:

|

“For the Jews there was light, gladness, joy and honor (Esther 8:16), so may it be for us!

“I will raise the cup of salvations, and I will invoke the name of Hashem:”

|

לַיְּהוּדִים הָיְתָה אוֹרָה וְשִׂמְחָה, וְשָׂשׂוֹן, וִיקָר. כֵּן תִּהְיֶה לָּנוּ:

כּוֹס יְשׁוּעוֹת אֶשָּׂא, וּבְשֵׁם יְיָ אֶקְרָא:

|

So I then lift my drink. Today day we need to brown-paper bag it, since we are out of the kosher grape juice. We will have to exchange out one the blessing for wine with the appropriate blessing for beer (she’hakol).

As I lift my drink and at the right moment along with the words of the ritual. And I say the words of respect and reverence: “Savri maranan ve-rabanan ve-rabotai / By your leave my masters, teachers and gentlemen…” Words which ask permission of my guests for me to bless before them.

Photo Credit: Zero-Renton Prefect

But also mystically, when we say the savrei maranan – it is meant to symbolize a deferring of reverence to our Jewish sages, rabbis and masters who have gone before us. We acknowledge that through their teachings and traditions they gave us, that they still are living to us and with us. I show respect to them before I proceed.

Standing here I raise my drink as I also make a toast to my friends, family, my city and the historical Jewish heritage of Boyle Heights. And as I say these words, even my non-Jewish friends show their comfort and familiarity with this custom and respond with the traditional response: “L’Chaim! To life!”

Now it is the Jewish custom to bless, over a cup which is filled as near as we can to overflow. So that our joy should be the same, spilling and running over. (Psalm 23:5) And it really seems to, as I say the blessing over the drink.

Next we take the bundle of spices. Made from an etrog – an Israeli citron used during the Sukkot holiday for the mitzvah of Lulav right here in the eastside community – which was dried with cloves, as a spice-box. I say the blessing over the basamim; the fragrant species, the spices and herbs.

The Jewish tradition says that an extra soul is given to each Jews for the celebration of Shabbat, an additional soul to have twice the joy! But when the sabbath leaves us, so does this extra soul. This transition from the hight of joy to the lowly place of mundane life can be deflating. But in order to awaken our spirits anew, to rouse them to attention we use these spices. They are our traditional smelling salts, but they are instead intended to help arouse our common soul to life once again. Pleasantly reanimating us after our long day of Shabbat celebration. We each take a moment to deeply inhale this fragrance, passing it around the circle.

Next Jesse draws the candle low, within reach of us all, as I say the next blessing; “borai morai ha’aish.” As I bless G-d who creates the illuminations of fire. Tradition says that fire was created on the first Saturday night, at the end of the week of creation. (Pesachim 53b) When G-d gave Adam, the first man, the knowledge to rub stones together and create fire. We recall this act now, commemorating that very moment in order to reenact the wonders of creation, in which we are also active partners. I meditate upon this hope now, that G-d may likewise continue to give us the knowledge to continue to do awesome works of creation in this world.

And now near the flames we all hold our hands close and cup them, to see the light passing through the tips of our fingers. Not between them, but shinning through the translucency of our fingertips. For a movement I consider how the spiritual world and the Divine, it is hidden from view. We can only merely perceive this realm of spirit as a flame, the reality of which shines through from within our own holy being, as through good deeds this holy light emanates outward from within us all.

And now near the flames we all hold our hands close and cup them, to see the light passing through the tips of our fingers. Not between them, but shinning through the translucency of our fingertips. For a movement I consider how the spiritual world and the Divine, it is hidden from view. We can only merely perceive this realm of spirit as a flame, the reality of which shines through from within our own holy being, as through good deeds this holy light emanates outward from within us all.

So for a moment I again make a mystical reflection as I look at these hands which I try so hard to use for good deeds. The Zohar, the main mystical text of Kabbalah which interprets the Torah, it tells us that when G-d first created man we were beings of pure light, translucent bodies which were “clothed in light.” And that from the depths of us, our souls would shine brightly to the surface from within. But that after the sin of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, the consequence was that people lost their vestiges of pure light and became beings of mortal flesh. However, this tradition tells us that G-d let humans keep a reminder of our former state, in the translucency of our fingertips.

When I hold my fingers close I remind myself of this truth, that I am a being of light. A light in this world and this community, a light which will shine through to the outside world through my tireless work I perform with these very hands. This is a truth I strive never to forget.

The streaming passers still taking notice as we huddle together into a warm circle for these moments. Then once again we raise the candle and the cup high! And I begin the concluding words of the ritual (which are the same in all traditions, Ashkenazi and Sephardi):

|

“Blessed are You, Hashem, our G-d, King of the Universe, Who distinguishes between holy and secular, between light and darkness, between Israel and the nations, between the seventh day and the six days of labor. Blessed are You, Who distinguishes between holy and secular.”

|

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ, אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם, הַמַּבְדִּיל בֵּין קֹדֶשׁ לְחוֹל, בֵּין אוֹר לְחשֶׁךְ, בֵּין יִשְׂרָאֵל לָעַמִּים, בֵּין יוֹם הַשְּׁבִיעִי לְשֵׁשֶׁת יְמֵי הַמַּעֲשֶׂה, בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ, הַמַּבְדִּיל בֵּין קֹדֶשׁ לְחוֹל:

|

I really consider these words deeply each and every time. The word that stands out to me is the key word of this ceremony, hamavdil. The word hivdil – in Hebrew, it means to distinguish.

We draw our understanding for this word from the Torah, from the book of Leviticus which contains the holiness code; there we are told to be holy, and to be distinguished people. There we are told to separate ourselves and stand apart, to be holy by keeping the Torah laws which keep one sanctified (i.e. keeping kashrut; Leviticus 20:25; 10:10; 11:47). This word likewise brings to mind how on Shabbat the Jewish people are to separate from the world’s secular activities and all its toils and embrace the joy of the sabbath. That it is as different as the difference between light and dark, this embracing of the sacred over the “profane.” And so too, as a people who keep these ways we are distinct and unique because of these practices.

We draw our understanding for this word from the Torah, from the book of Leviticus which contains the holiness code; there we are told to be holy, and to be distinguished people. There we are told to separate ourselves and stand apart, to be holy by keeping the Torah laws which keep one sanctified (i.e. keeping kashrut; Leviticus 20:25; 10:10; 11:47). This word likewise brings to mind how on Shabbat the Jewish people are to separate from the world’s secular activities and all its toils and embrace the joy of the sabbath. That it is as different as the difference between light and dark, this embracing of the sacred over the “profane.” And so too, as a people who keep these ways we are distinct and unique because of these practices.

Lately, I feel that far too many times when religious people speak regarding this they focus far too much on the idea of separating themselves from that which they feel is “profane.” From people and a society which they feel are less than kosher; less than sacred. But I don’t believe that is what it should actually mean to us, here and in this place. In this place with this mixed assembly of people; Jews and non-Jews, religious and secular, cultured and counter-culture.

The word hivdil means to distinguish. It’s often used in everyday speech to contrast one thing to another, not to really compare as there is no real comparison. As they aren’t really meant to be compared against. But it doesn’t just mean that, it also means that you can tell something apart from the rest. You can tell what it is, as it stands apart and is recognizable for what it is. I remind myself that I am special as a distinct person as a Jew, and so is each of these friends of mine distinct in their own way.

Zero-Renton Prefect, Shmueli Gonzales, and Jesse Elliott.

Again, I bring our attention back to the candle. To recognize that life and the world is like this braided candle. There are certainly distinctions in the world and between people, but in our own ways we are unique lights in the world; just like each wick upon this braided candle. Though we must allow ourselves to be intertwined! Just like Shabbat is intertwined with the work-week, we must have one in order to have the other! We need to have a partnership between the sacred and secular. We could not have the joy of the sacred, without the labor of the week and its secular duties. So too, the sacred and the secular both have their place and their time to shine.

But now as this joy of Shabbat must come to an end, we must hivdil – we must separate – from the radiant light of a most holy Shabbat and begin our toils anew. And as the blessings of havdalah come to an end, I drink from the cup and I extinguish the candle with a pour of drink over the flames. Putting out the light of Shabbat until next week.

And as we make our way back home to the eastside over the bridge I begin to sing the traditional songs. Among them are “Am Yisrael Chai” and “David Melech Yisrael.” Songs of life! And as we pass the old Jewish sites, we remind ourselves that the works of the Jewish people and the joy of Jewish life are still flickering to life here. And keep in mind that the spark of this Jewish heritage needs to remain alive, to continue to contribute to the diversity which has enriched Boyle Heights for the past century. To show some continuity in the community, where change and modernity seems to quickly be making many things around here all but a memory.

The canopy of beams and girders of the Sixth Street Bridge, by daylight. She is set for demolition in 2015.

But sadly, even this last-stand act of havdalah is going to change for my circle in the near future. After all these years of hanging out at the Sixth Street Viaduct, I’m sorry to announce that the bridge is being demolished.

This iconic bridge which has graced the Los Angeles landscape since 1932, she is suffering an alkali-silica reaction in the concrete (called “concrete cancer” by engineers). This reaction creates cracks in the concrete, which are now seen covering all over the body of the structure. With a 70% probability of coming down in the next major earthquake, this most famous of Los Angeles sites is being demolished. It will be closing this Spring of 2015 and demolished in the following months, to make way for a newly designed bridge which is expected to open in late 2019.

So where will we perform havdalah in the future? I don’t know. Now, it’s not that we haven’t tried other spots for havdalah. But they don’t feel the same, and this is where people know to come and join in if they want to. It’s going to be interesting to see if I can recapture this spirit elsewhere.

A Touching Personal Experience from This Past Week

Let me give you one last precious story, from this past week. A special havdalah which really touched me.

This past week my dear friend Irv Weiser calls me while I’m on the bridge. He calls right as the boys are heading back, because as non-Jews they had plans for a ham related holiday feast! Oy, what a dilemma! I was sure I was gonna miss havdalah on the bridge this week, the ceremony which closes the gates of Shabbat. In the face of the rare occurrence of not having any participants, I was thinking I’d have to do it back at the house on my own.

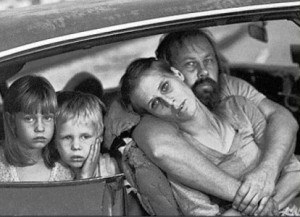

Punk Rock Havdalah, in Los Angeles. Shmuel Gonzales and Jesse Elliott. Photo Credit: Zero-Renton Prefect

But Irv calls me and says to stick around. That he was just a few blocks away having coffee with a Mexican Jewish man, a homeless friend of his from the eastside. They were wondering if they could join me for havdalah. So we went up and they said the blessings of havdalah with me.

Irv, was born and raised Orthodox Jewish in the neighbourhood of Boyle Heights. And educated at the Breed Street Shul and local yeshivot. He says he’s agnostic now. But as I begin the ceremony he starts to join in the Hebrew prayers. And tell me touching stories of his parents, who were holocaust survivors and who came to Boyle Heights after the war to join a relative already here. He related to me how his parents used to perform the ceremony, and how they pronounced the words in their Eastern European accents.

He then takes a look at the skyline and across the bridge, which he hasn’t seen that way since he was young… now he’s in his 60s. But all the more he’s in awe of the sight after all these years.

For a few moments I also got to talk about the significance of the ritual up there on the bridge with this new friend I’ve met through him, as my buddy Irv gets thrilled by my knowledge and passion. And willingness to take the time. (And in a caring manner nagging me why I don’t study for the rabbinate already, that’s the story of my life!)

As we completed the ritual with song and stories, Irv thanked me for keeping Jewish tradition alive here in this way. As a means of keeping the memory of the legacy of classic Boyle Heights alive, even today after the once predominate Jewish community started migrating away from the neighborhood some 50 years ago.

Irv also expressed his gratitude to me, for investing myself into nurturing the future Latino Jewish community on the eastside. A growing community of Jewish Latinos, who are noticeably becoming integral to the future of Jewish expression here and in our local synagogues.

Irv’s been texting me since. And he keeps telling me, interestingly and touching coming from a self-proclaimed “cynical” and “bored” Jewish agnostic, “Havdalah… the prayers… and that place on the bridge. Now that is really spiritual, and most memorable.”

How to perform Havdalah with alternative items:

-

Though it is most common to make havdalah over wine or grape juice which requires the blessing “pri ha-gafen,” (fruit of the vine) one may also say havdalah over any type of pleasant drink if kosher grape juice is not available; anything except for water or a common drink like soda (according to Rav Moshe Feinstein), which is meant mainly to quench thirst. One should pick a drink which is considered a sociable drink. This can include even coffee or tea (with or w/o milk), or other fruit juices. However, Sephardic rabbis such as Rabbi Ovediah Yosef suggest that the use of intoxicating drinks such as wine, beer, etc. is choicest. One should say the appropriate blessing for what ever drink you choose, in place of the blessing for “pri ha-gafen” (fruit of the vine) when noted in our siddurim.

-

If you do not have a havdalah candle, all you need to do is find two candles and hold the wicks together. Pick a couple of friends out and have them hold the candles with the wicks touching through-out the havdalah ceremony. This is also a great way to physically display how our individual lights are so much stronger when people come together in unity.

|

About the Author: Welcome to Hardcore Mesorah! My name is Shmueli Gonzales, and I am a writer and religious commentator from Los Angeles, California. I dedicate the focus of my work to displaying the cultural diversity within Judaism, often exploring the characteristics and unappreciated values of Chassidic and Sephardic Judaism. Among my various projects I also produce classical liturgical and halachic texts for free and open-source redistribution.

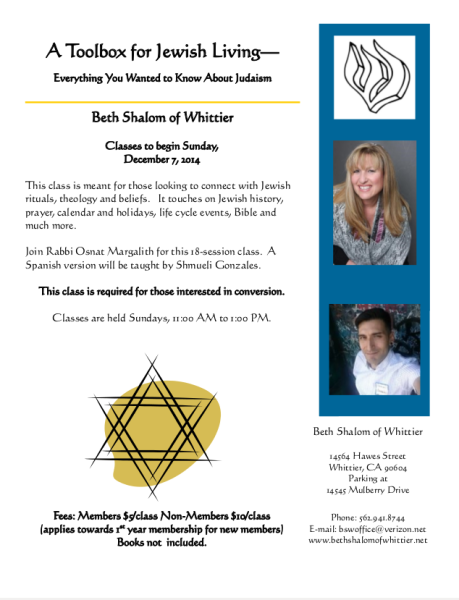

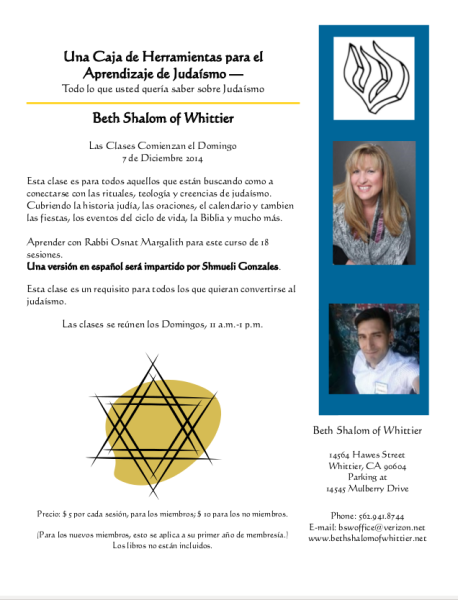

I am a proud member of Congregation Beth Shalom of Whitter – a modern-traditionalist Jewish congregation – where I also teach “Introduction to Judaism” and coordinate Spanish language programming for our growing Latino Jewish community here in the Los Angeles eastside and the San Gabriel Valley.

|

Recommended articles: