Taking steps daily on our journey towards freedom

We now find ourselves in Chol haMoed Pesach – the intermediate days of Passover, the middle days of this ongoing eight-day holiday. After a grueling week of preparation and a very energetic first two festival days, we are all physically spent, ready to relax and enjoy the rest of the week to come.

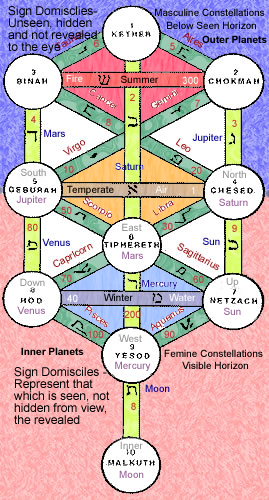

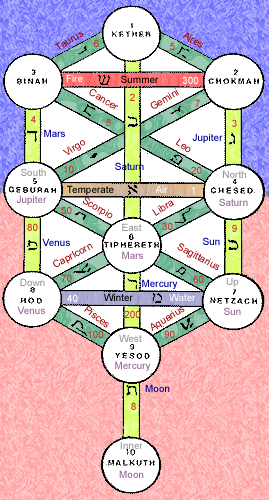

MITZRAYIM TO HAR SINAI: In this Sefirat haOmer chart one envisions themselves taking 49-steps up the summit of Sinai in time for Shavuot. Designed by Aharon Varady, a realization of a concept envision by Andrew Ross z”l.

Still for many people the joy of the festival and that sense of momentum in our souls remains with us. As we each work through own personal exodus during this season. Now that we have determined to become free people, naturally there is a new passion to experience and actualize that freedom. And to continue this spiritual journey to become more liberated. A desire to push forward in this march of freedom still inspiring many of us.

So how do we do that? How do we become more free and more liberated people?

And how do we satisfy this expansive drive aroused in our souls, while also being amidst an exhaustingly vigorous season?

Our tradition responds to this with the mitzvah of the Sefirat haOmer – the commandment of counting of the Omer. And through this tradition we learn how everyday we can do a little bit of work on improving ourselves. That’s all it really requires to pursue freedom within yourself, just taking a small step each day out of whatever has held us back in our life’s journey.

In the procession of the Jewish year, we are on a journey from Pesach to Shavuot. A journey which takes us from bondage in Egypt, and brings us to celebrating freedom and receiving the Torah at Sinai.

We’ve talked before about the biblical commandment, to count seven weeks of harvest gladness in which our ancestors were to offer up their coarse barley growth. And how on the fiftieth day the ancient Israelites would offer up an offering of their finest wheat in the Temple, in order to bring great culmination to this spring season on the holiday of Shavuot – the festival of weeks, celebrated on the 50th day from Pesach. (see “The Sefirat haOmer: Making The Days Count“)

These two holidays of Pesach and Shavuot, along with a third agricultural festival of Sukkot in the fall, they are called the Shelosh Regalim. These were the three pilgrimage festivals of the Torah, which in ancient times required people to journey all the way up to the capital of Jerusalem every year for these holidays.

This holiday of Shavuot has no fixed date, it occurs after 49 + 1 days after Pesach. Nor did this holiday historically have any fixed religious significance until the rabbis of the Mishna began to relate this holiday with the giving of Torah at Har Sinai.

The rabbis therefore understood these 49 days as a time of personal preparation for receiving Torah. A period which would come to be characterized by personal reflection and ethical introspection. In this way the rabbis made this period an inner journey for us. They helped us appreciate this extensive mitzvah of Sefrat haOmer as a process on a path to become worthy of receiving this revelation of Torah. In order to stand dignified at Shavuot and receive this Torah anew.

In this way we also come to appreciate the sefirah period as a way for refining and cleaning ourselves up along the way – as we shed our slave characteristics – on our way to the reception of the Torah at Sinai.

This sense of devotion became even more stressed by the kabbalistic masters of the 16th century in Tzfat, and then later by the chassidic masters who followed them. These mystics also decided take the journey inward, but in a much deeper and more profound way.

According to their custom of meditating upon the prayers of their highly mystical siddurim, they gave practical application to the Sefirat haOmer for making it engage a personal tikkun – a correction, a repair in one’s nature. And to do so systematically and with motivated intention.

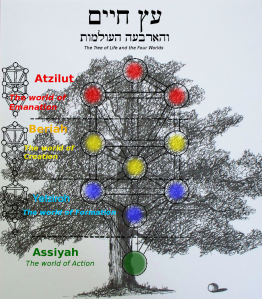

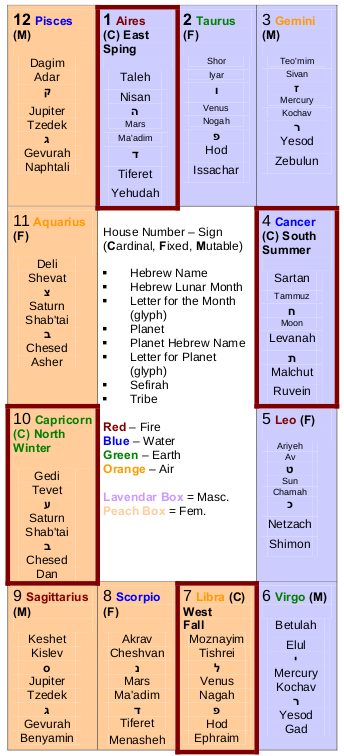

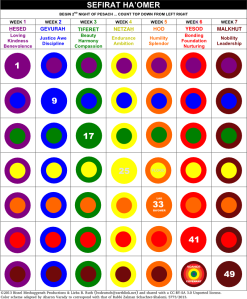

The mystics broke the sefirah period into seven cycles of seven weeks, seven being the number of completion and wholeness (i.e. number of days in a week; creation). Each of the seven weeks were set to correspond to one of the seven sefirot (Divine forces) which active in the physical world. Likewise each day of the week was set to correspond to a sefirah as well, making us look even deeper into each of these characteristics within ourselves.

This form of meditation reflects upon seven essential characteristics, and then makes us further consider how we operate those creative drives. We learn to focus on specific points of our character.

Let me give you a few examples of how this line of meditation works, and also demonstrate how one can reflect on these (with a few off-the-cuff meditative suggestions that come to mind for me during my personal reflection at this time, those are in quotes; to give us examples of how to work through these thoughts):

Day 1 of the Omer:

חֶסֶד שֶׁבְּחֶסֶד

Kindness within Kindness

“Do I display my kindness with acts of truly pure kindness?”

Day 2 of the Omer:

גְּבוּרָה שֶׁבְּחֶסֶד

Discipline/Judgment within Kindness

“Is my sense of discipline in-line with my sense of kindness?”

Day 3 of the Omer:

תִּפְאֶרֶת שֶׁבְּחֶסֶד

Beauty/Harmony within Kindness

“Do I use my expansive kindness for bringing harmony and balance?”

Day 4 of the Omer:

נֶצַח שֶׁבְּחֶסֶד

Endurance/Victory within Kindness

“Is my sense of kindness in-line with a love that is long-lasting and able to overcome the challenges?”

During the first week we start in Chesed (Kindness), which is an accessible point of reference for the soul as we continue on with the joy of celebrating Pesach and as are just starting out on our sefirah count. Then in the second week we move into Gevurah (Discipline/Judgement). The third week Tiferet (Beauty/Harmony), etc.

Each week we look at one part of our Divinely inspired nature, and then systematically examine how we can bring balance to it. Looking at each level of our consciousness, realizing there are elements of each impulse mixed-in with the others. Our challenge is to bring balance within ourselves so that none of these are in conflict, and so that we can achieve a sense of freedom within ourselves.

This might also be helpful for beginners of this form of meditation: Think of the daily sefirah as representing one aspect of your divinely inspired inner drives or ambitions, and the sefirah for the week as representing how you go about achieving that in your actions. There is certain ways we feel inside, but its all about bringing our outward displays in-line with that.

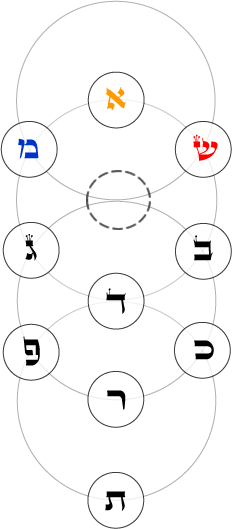

The kabbalists weaved other meditative elements into their counting of the Omer. They also assigned certain meditative words from psalms and letters to each day. As well as pieces of the highly mystical Aramaic prayer Ana Bekoach. All these textual overlays, to further inspire an inner journey.

Now there is a reason that I keep referring to the Sefirat haOmer as a journey. This mitzvah is one with many steps in order to fulfill it. It requires us making the effort everyday for 49 days, taking many small steps everyday. We cannot move forward if we stop at any point. Which is what makes this mitzvah so much of a discipline to keep. However, it is a deeply rewarding journey of self-exploration and refinement for those who follow all the way through!

Modern Meditative Aids for the Sefirat haOmer

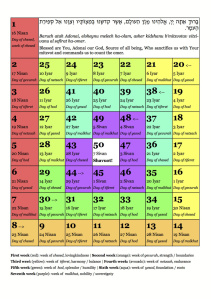

One of the best ways to help one remember the daily Omer count is to use a chart. Over the years many charts have been devised to help people remember and stay accurate with their count. Many communities and homes have unique ones which people festively display and refer to.

One of the best ways to help one remember the daily Omer count is to use a chart. Over the years many charts have been devised to help people remember and stay accurate with their count. Many communities and homes have unique ones which people festively display and refer to.

These clever charts are also very useful for helping people visualize this path and process. One contemporary chart posted by Rabbi Rachel Barenblat of the ALEPH: Alliance for Jewish Renewal is a personal favorite. See her entry at Kol Aleph:

This not only a great way to keep count, it is also a great way to meditate upon the Omer. To think of it as a journey moving inward, to examine ourselves in our deepest core. Or we can also see this as a path around a mountain, moving upward with a step each day until we reach the peak of Sinai. This lovely chart is also overlaid with other meditative elements which color and desktop formatting today allow.

Over the years I have made the case that the rabbis made intentional use of specific words, letters and sounds to deliver imagery. As they were limited in their means of presenting these ideas in a black-and-white world in which they produced their manuscripts, the mystics used other schemas. I have always believed that had the mystics of old lived today they would layer meaning in color, which would also aid in showing relationships of one thing to another.

I’m glad to see that several scholars and rabbis of the modern age are utilizing color to expressed concepts in their works and materials. To help people visualize the lesson and their inner journey.

One the finest examples of this is the Sefirat HaOmer Chart of Lieba B. Ruth (aka, Lauren Deutsch), which was originally created according to her own color scheme.

One the finest examples of this is the Sefirat HaOmer Chart of Lieba B. Ruth (aka, Lauren Deutsch), which was originally created according to her own color scheme.

Aharon Varady also notes:

“Lauren Deutsch’s system of color correspondences for the sefirot mainly follows the light spectrum from red to deep blue, then black and purple. Her systems accords well with that of Mark Hurvitz’s 7×7 Color Grid for the Omer.”

My friend and colleague Aharon Varady of the Open Siddur Project, was able formulate a meditative chart which would alternatively correspond to the color schema innovated by Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi.

She has generously shared this Kabbalistic Sefirat HaOmer chart as free and redistributable resource through the Open Siddur Project. Please re-distribute!

Please also refer to the original post by Aharon Varady and Lauren Deutsch at Open Siddur Project:

This chart expresses how the sefirot – both for the corresponding week and day of the sefirah count – how they come together. Causing us to conceptualize and consider the relationship of one characteristic to the other, and helping us visualize the balance we are trying to achieve between these powerful forces inside us.

In like manner, Aharon Varady also created a variation of the meditative circles chart utilizing a classical and historically inspired color schema. A schema which was presented in Reb Seidenberg’s Omer Counter widget (Neohasid.org). Aharon noted that this color system corresponds closely with that of the colors suggested by the RAMAK in Pardes Rimonim, as cited in Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s book, “Meditation & Kabbalah” (p. 181) in the chapter titled “Colors.”

as cited in Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s book, “Meditation & Kabbalah” (p. 181) in the chapter titled “Colors.”

Having also taken personal interest in the color correspondences within classic kabbalistic literature, I had also tried to imagine this. To perceive how the mystics would have conceived of this. So this additional contribution has helped bring that to life for me. This color schema is very useful and meaningful to both Chassidic and Sephardic followers of the mystical disciplines.

The meaning of all this is also presented for us by Aharon in his detailed comments of the aforementioned post. The entry also wonderfully included the prayers, blessings, meditations, and even an updating counting widget… in addition to the helping you identify and visualize the interacting sefirot as you observe this special mitzvah!

Conclusion:

Many of us modern people don’t have the time or space in our lives make a religious pilgrimage like ancients used to during this time of year, therefore we have a long tradition of focusing on how to take this journey inward. We should utilize the many ways of teaching and thinking which helps take us on a journey for the soul.

Want to personalize your own journey? Here is a Do-It-Yourself help for making your own Sefirat haOmer Chart.

We have been learning about this inward journey through the soul we engage in during the sefirah period. One of the best ways is to visualize that journey as path up a mountain, as previously mentioned regarding another chart.

Aharon Varady also provides us with a subtle adaptation of a chart concept envisioned by Andrew Ross z”l. As noted by Aharon elsewhere:

“Mark Hurvitz wrote: “Rabbi Amy Scheinerman‘s father (Andrew Ross z”l, a graphic artist) arranged the squares in a spiral. If you look at it in three-dimensional space we begin at the foot of Sinai and climb up to the summit in time for Shavuot!” (Please see: http://www.scheinerman.net/judaism/shavuot/omer4.html)

This wonderful chart is designed by Aharon Varady, a realization of a concept envision by Andrew Ross z”l.

The chart image shown at the top is a Creative Commons document, editable and redistributable design. Showing a spiral starting from the upper right, and moving counter-clockwise on its way inward. Indeed, all the items presented by Open Siddur are open-source licensed to edit and share! Feel free to personalize it with numbers or meditative thoughts.

What are you making your exodus from this year? Are you trying to leave bad traits behind? Are you making a journey out of addiction? Are you finding liberation from the effects of unhealthy relationships? Or are you just stepping forward in order to leave a sense of apathy behind? Personalize this chart and meditation for your goals. Whatever helps you visualize your journey inward to the soul and upward to Sinai!

Related articles:

- Starting off the Spiritual New Year Right – Mitzvah-making Opportunities for the Spring and Summer

-

The Sefirat haOmer: Making The Days Count – an introduction, and the Blessings

-

The Menorah Psalm – Meditative Paths: Introduction to the Menorah Shiviti